Harlan Ellison: Short Story Collections

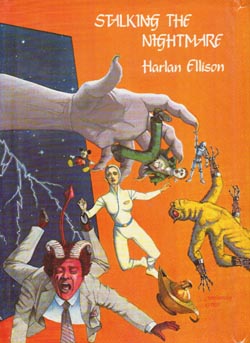

Stalking the Nightmare

![]()

Reviewed by David Loftus

1st Hardcover: Phantasia Press (1982) (reviewed edition)

1st Paperback: Berkley (1984)

Cover Art shown: Jane Mackenzie

The

Langerhans review

Reviews Description and Spoiler Warning

Dedication:

In every possible way

this book is for

(Ms.) Marty Clark

|

Contents and Copyright DatesForeword by Stephen King |

![]()

COMMENTARY

Stalking the Nightmare was published in 1982, during a period when Ellison wasnít putting much fiction between book covers. Partly, he was busy with other activities -- weeklong trips to France, New York, Boston, Denver, Michigan, and Florida for cons and workshops; labor on a screenplay version of Norman Spinradís Bug Jack Barron, which Costa-Gavras was interested in shooting; the inauguration of the Harlan Ellison Recording Collection with Shelley Levinson in early 1982. Legal headaches (a suit against ABC-TV/Paramount which he won in April 1980, Fleisher lawsuit maneuverings that dragged on for several years) also ate up time and psychic energy.

But Ellison also was grappling with an ideopathic medical disorder (translation: the doctors couldnít figure out what was wrong) that started in the late 1970s and resembled Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Typically, a terrible lassitude struck about mid-day, causing the writer to fall down and vegetate, perhaps retaining only enough energy to read. Ellison kept his condition secret for several years, fearing his sufferings and drastically reduced creative output would mean death in the marketplace.

Strange Wine was four years behind him, Shatterday two. Most of the other books from this period, and for a number of years to follow, were anthologies (Medea) or graphic retellings of older work (The Illustrated Harlan Ellison). Ellison also turned increasingly to columns and essays in the early í80s. But even essay collections (Sleepless Nights in the Procrustean Bed and An Edge In My Voice) would take another two to three years to hit the streets.

There is a certain amount of recycling in this book: seven of the twenty pieces originated in the 1950s, two in the 1960s, and three in the 1970s. (Four had been collected in the 1972 paperback Over the Edge.) That accounts for some of its unevenness. Stalking comes in as a somewhat better than average Ellison collection, largely on the strength of its nonfiction pieces. Itís not a bad introduction for the Ellison newbie: less relentless than Deathbird Stories, less bleak than Angry Candy, but not as strong as they or Strange Wine and Shatterday.

It certainly didnít hurt to get Stephen King to do the foreword. King praises Ellison for being a ferociously talented writer, ferociously in love with the job of writing stories and essays, ferociously dedicated to the craft of it as well as its art, and adds that the force of personality in his writing tends to make other writers, even King, sound like Ellison after reading him. Itís a little odd to have a writer not known for delicacy, subtlety, or brevity say he sounds like you (although Ellison himself might grant that of those three, his work has mainly brevity to distinguish it from Kingís), but King is right on when he says Ellisonís fiction has steadily broadened its area of inquiry and never declined in its energy.

For trivia buffs, King guesses the age of one of the stories, "Invulnerable," which was originally scheduled for inclusion but did not end up in the collection. (Ellison explains in a footnote that he felt it needed reworking, partly due to a dated quality King sensed in it, and he wasnít able to get to the job before it came time to ship the manuscript to the publisher. The author substituted the recent and excellent -- not to mention longer -- "Grail." ) A shame, because King adds that "Invulnerable" is his favorite, and I am not aware that it has ever been printed since.

Best lines from the King intro:

"Of some people it is said they will not suffer fools gladly; Harlan

does not suffer them at all."

"The cult of celebrity is cogitative shit running through the bowel of

the intellect."

and

"If I knew I was going to be in a strange city without all the magical

gris-gris of the late 20th century -- Amex Card, MasterCard, Visa Card,

Blue Cross card, driverís license, Avis Wizard Number, Social Security number

-- and if I further knew I was going to have a severe myocardial infarction,

and if I could pick one person in all the world to be with me at the moment

I felt the hacksaw blade run down my left arm and the sledgehammer hit me

on the left tit, that person would be Harlan Ellison. Not my wife, not my

agent, not my editor, my accountant, my lawyer. It would be Harlan, because

if anyone would see to it that I was going to have a fighting chance, it would

be Harlan. Harlan would go running through hospital corridors with my body

in his arms, commandeering stretchers, I.C. support units, O.R.s, and of course,

World Famous Cardiologists. And if some admitting nurse happened to ask him

about my Blue Cross/Blue Shield number, Harlan would probably bite his or

her head off with a single chomp."

One more trivia note: King decries the cult of personality, which brings many consumers to an authorís work because of who he is or what she does away from the typewriter or word processor, and makes them confuse the writing with the person. "I am sick of being told to buy books because their writers are great cocksmen or heroic gays or because Norman Mailer got them sprung from jail."

This is a reference to Jack Henry Abbott, and a book culled from his letters to Mailer from prison, published in 1981 as In the Belly of the Beast. Abbott, who had spent all but nine and a half months of his life beyond the age of 12 behind bars for passing bad checks and then killing another inmate (15 of those years in solitary), was paroled in early 1981. Mailer and others declared that he had promise as a writer and Mailer promised to sponsor him if he was transferred to a halfway house in New York City. The ex-con was out for only six weeks of being feted and praised before he fatally stabbed a black waiter -- an aspiring playwright and actor -- on Manhattanís Lower East Side. Abbott had read a lot, but he didnít know how to take a subway, buy toothpaste, or open a bank account. The killer went into hiding and was eventually captured in the rip-roaring oil rigger town of Morgan City, Louisiana Ö where I spent part of the summer of 1979.

That wasnít the last of Abbott, however. There was no end of people interested in using him and/or being used by him. Ed Bradley won an Emmy for an interview he did with Abbott on Sixty Minutes in 1983. In the Belly of the Beast was adapted for the stage and starred a young actor from the same Chicago theater scene as Malkovich and Sinise, named William Petersen. His performance impressed director William Friedkin enough to cast him as a crooked cop opposite Willem Dafoe in To Live and Die in L.A. (1985), and he would later play the first lawman-partner of Hannibal Lecter in Manhunter (1986). Things have been quiet for Petersen since, but in 2000 he struck gold with the surprise hit TV series CSI. Abbott, meanwhile, put out another book. But I digress.

Ellison also provides a fanciful introduction called Quiet Lies the Locust Tells, a fable about the value of storytelling, dreaming, art.

Synopsis

Christopher Caperton, an average American guy no more lucky in love than

the next, has been looking for True Love most of his life. He finds hints

of it in real women and sirens of the screen while growing up. In 1968, he

is making do in Saigon by dealing drugs to unhappy soldiers with his lover

and partner, French and Thai mix Sirilabh Doumic. She catches a piece of shrapnel

in a bombing, and during her lingering death tells him where to find the artifact

called True Love. It involves using some of her blood and a hair from her

head to conjure a minor demon called Surgat. The demon helps, and Caperton

moves on to Paramaribo, Indiana, Florida, Trinidad, New Orleans. In December

of 1980 he confronts the New York billionaire who currently owns the artifact.

And he must summon Surgat again.

Commentary

As Ellison mentions in the 1999 audio collection Voice From the Edge,

he put a lot of work into this story. It is one of his personal favorites,

and he feels it is underappreciated by most of his readers. "Grail"

is certainly the best fiction story in the book, though for sheer impact and

plotting, the first two essays beat it out, in my estimation.

The story captures the unnamable ache we often feel when young, but less when older and busy with distractions big and small, sometimes reawakened by a face on the street or in a film. I can appreciate the work he put into the story. It is well told, so far as it goes. But it still strikes me as a sort of elaborate shaggy dog tale. If a hero is shown ultimately to be a fool, what is the effect upon a reader who cared about him and his mission?

Reviewer's note: Early in the story, Chrisís drug sales are said to have netted "over a million and a half dollars." I would have written "more than," because "over" suggests non-quantifiable amounts such as water levels. But more irritating is the phrase "million and a half," whose like I hear all the time on broadcast news these days (usually in reference to the salaries of professional athletes). Technically, the phrase suggests Caperton had stowed one million dollars and fifty cents; the half modifies dollars rather than million. It would be more accurate to say "more than one and a half million dollars." But this is probably another losing battle on the language usage front.

THE OUTPOST UNDISCOVERED BY TOURISTS

Synopsis

Kaspar, Melchior, and Balthazar, having followed the shimmering star for

one thousand, nine-hundred, and ninety-nine years, make their way by Rolls,

stopping by night to inflate air mattresses and watch roller derby on the

tube, on the endless trip to the manger.

Commentary

A cute 4-1/2 page hoot with a dollop of Yiddish shtick, a little dated

(Sammy Davis Jr. only made it to 1990, and are Krugerrands still around?)

but still sweet.

Synopsis

Rike Akisimov, just handed a one-thousand-year sentence to the penal colony

on Io for unprecedented but unspecified heinous crimes, has made a break for

it and headed for the spaceport in search of a Driver to get him out of there.

He kidnaps a tall, tanned, and beautifully proportioned senior grade Driver

who does as he tells her, yet warns him several times "you donít want

to do this." Though a fairly simple and simply-talented psi employee,

she turns out to be right.

Commentary

A fairly classic science fiction plot, for Ellison. In fact, it first

appeared in a 1957 issue of Infinity magazine. Short, tidy, and not

terribly impressive, although itís nice to see a beautiful babe simple enough

to be referred to by the narration as a "girl" outwit a desperate

criminal.

THE 3 MOST IMPORTANT THINGS IN LIFE (Scenes from the Real World: I)

Synopsis

Ellison describes the items in the title, which are sex, violence, and

labor relations, and gives an illustration from his own life -- only minimally

exaggerated -- of the importance of each.

Commentary

This is the first of the essays in this collection, and it is one of

the most memorable and entertaining in all of Ellisonís nonfiction -- or fiction,

for that matter. Iíd rate it among the top 10 things Ellisonís ever written.

(Lessee, Deathbird, Maggie Moneyeyes, Norman Mayer, Boy and His Dog, Prowler

in the City, Paladin, Daniel White, Mother Serita, Repent Harlequin, City

on the Edge of Forever . . . well, top 15 or 20, maybe.)

The tales are not terribly deep, and donít even illustrate the philosophical points the writer says he wants to make, but that doesnít matter. They are great war stories, and the style is totally winning. As King writes, "one can almost see 'The 3 Most Important Things In Life,í as a stand-up comedy routine," which line of work Ellison once pursued for a time in the distant past.

The piece was first printed in the November 1978 issue of Oui magazine. There it is accompanied by a terrific illustration that does a riff on the old three monkeys seeing, hearing, and speaking no evil, with the name "punchatz" down in the corner. One wonders whether this was Ellisonís first encounter with Don Ivan Punchatz, who would execute a dynamite album cover for the recording of "On the Downhill Side" six years later. One also wonders whether Ellison submitted the essay anywhere else before some bright editor at Oui agreed to run it.

Besides the hilariously manic style, the essay is notable for unusual words (e.g., faunching and widdershins -- the latter was one of Ellisonís particular favorites in the Seventies), and literary and historic references (mene mene tekel, Tíang dynasty chopstick, tabula rasa, Potemkin) one is not used to encountering either in a porn magazine or in pop essays in general -- especially essays that use the word fuck.

I donít want to spoil anyoneís enjoyment by saying anything more about the content, except that despite the uniqueness of the events related in all three, I think the second one, on violence, is the most effective in terms of the writing. Its manic buildup (this one made me laugh out loud more than the others) to a thunderously shocking climax reminded me of something John Irving was doing at roughly the same time -- for instance, in the chapter "Walt Catches Cold" in The World According to Garp, and the scene in The Hotel New Hampshire where Sorrow, the stuffed dog, falls out of the closet and the grandfather dies of a terrified heart attack. It would be nice to know the identity of the other writer who was on the movie crawl and witnessed this incident.

The only other thing to be said is that Ellison really must record

this essay someday, perhaps for Dove Audioís Voice from the Edge series

and not just to confirm for posterity that he does a terrific Mickey

Mouse imitation. Absolutely phonographically perfect.

VISIONARY

(written with Joe L. Hensley)

Synopsis

Italian American narrator Whitelaw Martin had dreams from childhood of

a soaring cathedral in pinkish soil. He was a loner from a big family, sunk

in books growing up, and he joined the Force (formerly the Air Force, now

with its jurisdiction in the vacuum of space). The administration began to

give him tests and more tests. He found himself in a small, elite group of

six who were destined to travel far out there where no one else had been able

to go. Both he and a colleague suspected it had something to do with what

Charles Fort had written about ages in which certain things are destined to

happen -- because itís their time.

Commentary

A fairly by-the-numbers tale in the classic sci-fi style which was first

published in a 1959 issue of Amazing Stories. It has a measured calm

to it, without any great build to a crisis or surprise, which is uncharacteristic

of an Ellison story.

DJINN, NO CHASER

Synopsis

Danny and Connie Squires, a wisecracking Manhattan couple, have been married

only a few days and are shopping for furnishings at Connieís behest. Toward

the end of their day, looking for a taxi, they spy a musty curio shop which

seems to have materialized where there had been an empty lot only moments

before. The owner, Mohanadus Mukhar, a little man in a flowing robe and fez,

is having a sale and doesnít expect to be at this location for very long.

Connie spies a lamp, one very much like Alladinís, and asks Danny to buy it.

A spirited session of haggling ensues, Danny buys the lamp for a song, the

shop begins to waver and shimmer, and Mukhar shoos the couple out. The shop

disappears before the Squiresí eyes. That night, curiousity gets the better

of both of them and they begin to rub the lamp. A booming voice shakes the

building, crying, FREE AT LAST, but it doesnít grant any wishes. It proceeds

to make the Squiresí life a living nightmare, because the voice belongs to

an unhappy djinn, imprisoned in a cramped lamp by a sorcerer for at least

ten thousand years. Within a week Danny goes mad and ends up in a sanitarium.

But less than three days later, Connie shows up at the door, looking none

the worse for wear and actually dressed pretty spiffily, to take Danny home.

Commentary

This oneís a hoot, a rambling tale with a shaggy-dog ending. Both lead

characters crack lines like Ellison, but thatís okay. The story deals in cliches,

and self-consciously and good-naturedly admits it: "Isnít this what always

happens in weird stories where weird shops suddenly appear out of nowhere?"

Connie asks her husband. Best part is the dialogue during the haggling scene.

Synopsis

Sim (Self-contained Integrating Mechanical) is a robot that knows and

does a lot more than his maker realizes. Unbeknownst to Professor Jergens,

Simís been telepathically directing the simpler robo-scoots and other automatons

himself, and he has bigger plans. The idea is to have the robo-scoots kill

the professor, get the design plans, and make an army of robots like himself

-- only not quite as smart. But first he has to wait for the other guy visiting

the lab to depart. The visitor is a Lab Investigator whom Jergens hopes will

secure him more funding. Sim manages to implant a need in the visitor to leave,

even though Jergens wants to show him more, and then has the robo-scoots kill

the professor. Now he can become Master of the Universe!

Commentary

Another fairly quick and simple sci-fi tale (less than 5 pages), dating

from 1957 and Super-Science Fiction magazine, where it was bylined

with Ellisonís favorite pseudonym, Cordwainer Bird. A fairly knowledgeable

reader can probably guess the ending.

SATURN, NOVEMBER 11th (Scenes from the Real World: II)

Synopsis

This was installment 6 of the Edge In My Voice columns. It ran

in the March 1981 issue of Future Life.

Commentary

You may find detailed commentary on it in my Webderland

review of An Edge In My Voice.

Synopsis

After his final fight with his wife Gwen, Billy Dunbar, 38, took a hundred

dollars out to ride a Greyhound to the end of the world, which turned out

to be the beach at Wiscasset, Maine. There he confronts the dead from his

past -- the three grunts from the 2nd Battallion, 47th Mechanized Infantry

who bought it from a flying grenade near Bien Hoa City after Billy managed

to scramble out of the hole; the woman who walked into the Pacific near Malibu

while he was dating her and he didnít stick around to see whether she came

out -- and tries to sort out the lesson from the fact that he survived (usually

by running away) and they did not.

Commentary

Though well written and paced, "Night of Black Glass" is more

of a lyrical reverie than a story with any particular dramatic tension. It

doesnít do a lot for me. There is a mildly interesting interlude in which

a 10-year-old girl sits down and has a brief conversation with Billy about

sailing to the moon, but I donít see what it adds to the plot or meaning of

the story. I suspect Ellison merely had such a conversation with such a stranger

once.

Synopsis

A grisly trophy hangs in the club room of the Trottersmen, along with

the remains of all the other animals -- terrestrial and extra-terrestrial

-- shot by its members over the years, especially by Nathaniel Derr, who gave

the organization nearly $13 million. The story is that Derr, bored of all

the prey heíd hunted on Earth, paid a lot of money to tour the heavens in

search of wilder game, and eventually put down on the planet Ristable. The

inhabitants, a peaceful race of farmers who threshed the grasses of a quiet

planet to produce a sweet flour much prized by gourmets elsewhere, called

many things Ristable: their world, a significant weekly ceremony, and the

odd creatures that played a central role in it. Derr watched one of the ceremonies,

in which the horned, six-legged Ristable with vestigial tentacles stalked

a humanoid inhabitant and eventually killed him before a watching crowd, and

decided he could kill the creature if he took part in the event. So he did,

with results that surprised him.

Commentary

This story has a solid, straightforward narrative with some dramatic

interest, although itís not hard to guess the denouement. It comes from a

1957 issue of Super-Science Fiction.

Synopsis

Teddy Crazy, the host of a ratings-smashing late-night TV talk show, is

having a typical good night. He demolishes a harmless scientist working on

a federal grant, discredits a topless dancer and single mother of seven so

that the authorities deny custody and she commits suicide, and does similar

mischief until the final segment of his show, when His Satanic Majesty, the

Prince of Darkness, walks onto the set.

Commentary

A decent satire of contemporary bread and circuses for the masses. Published

in Adam magazine in 1968, it anticipates Howard Stern, Jerry Springer

and their ilk by several decades.

Reviewer's Note: Although the 1982 Phantasia Press first edition of Stalking the Nightmare is fairly clean, typographically speaking, the word affidavit is twice spelled incorrectly, as "affadavit," in this story. Despite its many other typographical crimes, Edgeworks II got this right.

Synopsis

Restless Dr. Alexander Cort, 35-year-old dentist, has run out on his practice,

his wife, and his children, and headed up Route 1 from Big Sur toward San

Fran. Last night he picked up a cocktail waitress and took her to a motel.

This morning he slipped out very early and stopped in to Monterey for breakfast.

But nothingís open. Thereís a heavy fog in the air, and at 7 a.m. itís still

dark out. The only available light seems to be coming from a bookstore. Cort

looks in the window and sees itís filled with people, but nobodyís turning

pages, or picking up and putting down books. Theyíre all just staring at a

pair of open pages, each to his or her own. Cort has an uneasy feeling about

this, especially since heís been to Monterey before and this sure isnít Monterey,

but the little old lady proprietress draws him in, saying, "I have it

here for you."

Commentary

Like "Djinn, No Chaser," this tale knowingly and self-consciously

toys with cliches. That can be a risky business; it ups the ante for the storyteller,

who has to outdo the cliches to make it worth the readerís while to wade through

them. Ellison does all right, but not surpassingly well at this. Itís perfectly

obvious to Cort that the store means trouble, particularly once the proprietress

informs him itís her job to give people just the answers they were looking

for (the two pages devoted to examples of customers who got what they wanted

are the first high point in the story), and that once they have them they

have nowhere else to go. In Cortís case, the woman can identify the best moment

of his entire life -- clearly a poisoned gift any way you look at it. So how

is Ellison going to give Cort what he wants and get him safely out

of there?

That Cort stumbles on one of the womanís weak points and they engage in verbal combat is a good narrative move, and the storyís second high point (although the quoted reference to The Treasure of Sierra Madre strikes a bit of a false note in her mouth and perhaps is not as refreshing today as it might have been in 1981, when the story debuted in Amazing Stories). I think "The Cheese" comes to a decent close -- it makes its point -- but I fear Ellison too easily provides his protagonist with cake and the ability to eat it.(What happened to the other awakening store customers? Presumably they stay, but itís unkind of the narrative to wake them up three pages from the end and then never mention them again.)

Typographical note: A possible symptom of early publisher dependence on computer word processing turns up in the paragraph about Sulayman the Magnificent (pages 207-208 in the first edition, 160 in Edgeworks). Twice the text refers to something coming íround again, and instead of an apostrophe to replace the missing "a" in around, thereís a single open quotation mark. This is a pitfall for unimaginative word processing softwares, because they donít realize apostrophes sometimes come at the beginning of a word. Too bad the editors at Phantasia didnít catch that. Again, Edgeworks II got this right.

SOMEHOW, I DONíT THINK WEíRE IN KANSAS, TOTO (Scenes from the Real World:

III)

Synopsis

This essay relates the story of Ellisonís failed 1973 Canadian television

series The Starlost. A producer named Robert Kline approached Ellison

to write a science fiction series that would be backed by 20th Century-Fox

and the British Broadcasting Corporation, and shot in London. This sounded

promising, so our hero described a plot situation he wanted to do. Ellison

refused to write a prospectus without being paid, but Kline cajoled him into

dictating the idea into a tape recorder, promised not to have the contents

transcribed, and immediately had them transcribed. The producer failed to

sell the BBC on the concept, but the Canadian Television Network bit. Now

it would be made in Toronto.

A big complication was a pending strike by the Writers Guild of America. (A smaller one was that Kline just assumed Ellison would move permanently to Toronto for the show.) Being a member of the guild board and very pro-union, Ellison refused to write for the show during the strike, despite many threats and some surprising bribe offers. For a while Kline secretly brought in another writer, but Ellison found out and put a stop to that. The Canadian Writers Guild was persuaded to accept the project as a wholly Canadian-produced series, so Ellison could work on it without technically violating the rules of the American guild. Goofy ads that violated basic laws of physics were put out, sets and "fashioning materiel" (costumes?) were generated based on an erroneous show bible written by the scab writer, and the whole thing got weirder and more stupid by the week. Ellison finally demanded that his pseudonym Cordwainer Bird be slapped on the credits, and the awful enterprise tanked.

The author received what he felt to be several forms of vindication when: 1) Kline appealed to Gene Roddenberry for help, and that eminence grise said he should have listened to Ellison; 2) the trial board of the Writers Guild judged Ellison not guilty of scabbing; and 3) Ellisonís original, unfilmed teleplay for the pilot of The Starlost -- "Phoenix Without Ashes" -- won the Writers Guildís best dramatic-episodic script award for 1973 in a blind judging competition against other final nominees from The Waltons, Gunsmoke, Marcus Welby, and The Streets of San Francisco.

Commentary

This story speaks pretty much for itself. In the opening paragraphs,

Ellison attributes the following remarks to Charles Beaumont, scenarist of

many memorable episodes of the original Twilight Zone series: "Attaining

success in Hollywood is like climbing a gigantic mountain of cow flop, in

order to pluck one perfect rose from the summit. And you find when youíve

made that hideous climb youíve lost the sense of smell." (Whadaya wanna

bet Beaumont didnít use the words "cow flop"?)

Ellison makes some lively comparisons of the production companyís shenanigans

to the Mad Caucus Race in Alice in Wonderland and a Balinese Fire &

Boat Drill. Lest anyone be tempted to regard this tale as an illustration

of one writerís hubris and irascibility, Ellison refers the reader to accounts

of similar debacles: Merle Millerís account of the evisceration of his 1964

series, Calhoun; James Gunn and The Immortal; the 1981 anthology

series Dark Room.

One small editing note, in the sixth paragraph from the end: the passive form of the verb "to lobby" is not "lobbyed." This was corrected in Edgeworks II.

Synopsis

Rondell, the last thief in a world where stealing is utterly pointless,

wakes up to the sound of a police helicopter and bullhorns outside his 32nd

floor hotel room. After his dramatic escape, he makes his way to the casino

and the office of its owner, the Professor. The Professor had found Rondell

as a 3-year-old in an orphanage, raised him, trained him for 19 years, and

had him steal jewelry (for no apparent reason) for 3 years. Then Rondell spent

a year in preparation for the Change Chamber, escaped, and has spent the last

5 years hiding in Sumatra. He has returned to confront and kill the Professor.

The casino is an ingenious place. Gamblers play against androids; if they win, they get to kill them. If they lose, they are killed. The odds are stacked against human gamblers because the casino is a government-sanctioned method of population control. Let them play themselves to death, is the concept.

Rondell nearly plays his mentor to the death, but the Professor convinces the younger man that the answers to his fate lie in the Slum, a locale of bogus mystery and poverty for the entertainment of people in an otherwise perfect world, and with a woman named Elenessa. With her, Rondell discovers the meaning of his training and existence.

Commentary

This is a decent thriller, though I detect some false moves in it. Originally

titled "School for Assassins" and appearing in a 1957 issue of Amazing

Stories under the byline Ellis Hart, it has one of the classic weaknesses

of its era: much of the plot movement consists of people telling one another

what happened and what the truth is. For an action story, too much of the

plot development consists of explanations in dialogue form. As the writing

coaches say: show, donít tell.

The Shakespearean phrase "Full fathom five" sounds odd in the mouth of a cat burglar trained for years in the martial arts and thievery. Itís certainly not common linguistic coin. Itís odd and ungainly to say that a person was "persecuted . . . studiedly." How does a person subside into "a vicious silence"? There is something almost laughable about a bingo game to the death, and I canít say it does a lot for me in terms of dramatic tension when a battle progresses via I-16, 0-33, B-7, and so on.

Edgeworks corrected a clumsy bit of proofreading in the original Phantasia, which read: "What do you mean, ĎFetch us?í" Since the line of dialogue is asking about another personís comment that was not a question but a statement, the question mark belongs between the single quote and the double quotes. One typo that survived from the Phantasia edition to Edgeworks was "Iíll forego my fun and take you out right here." What the text should have is forgo, which means to go without; forego signifies to go before, to precede.

Synopsis

Harlan Ellison agrees on very short notice to substitute for Jerry Pournelle

as the guest on Mike Hodelís Hour 25 -- the hour that stretches -- on KPFK

in Los Angeles. For an hour and a half he entertains ideas for stories from

callers which he tries to spin into plausible short story plots. Then a mysterious

caller pitches a fantastic tale that seems a little too real.

Commentary

This is a sneak-essay masquerading as a short story. It reads like the

transcript of an Hour 25 show, for the most part. Iíve never heard any segments

of Hour 25 to know how closely it resembles an actual broadcast, but this

one names names, not only of the showís crew but of most of the people who

phone in. Perhaps itís one of those quickie stories Ellison devised in the

window of a bookstore. The final woo-woo item, five minutes of conversation

between Ellison and the mysterious caller which supposedly takes a full half

hour, apparently qualifies the story as fiction. Mildly entertaining as its

wisecracks and idea-spinning are, "The Hour That Stretches" strikes

me as something of a cross between a lazy ego-stroke (the repeated references

to engineer Burt Handelsman being in stitches because of Ellisonís wit get

a bit tiresome) and a sincere tribute to the late Hodel.

Synopsis

Driving home from a New Yearís Eve party at the start of 1973, narrator

Harlan Ellison muses about the recent death of President Truman, who seemed

to forecast his own death ten years in advance, and wonders whether he could

guess when and how he himself -- Harlan Ellison -- would die. Thereupon he

relates ten scenarios -- three detailed ones and seven short single-paragraph

alternatives -- of his own mortal passing.

Commentary

This was actually a column for the Harlan Ellison Hornbook, in

the January 4, 1973 issue of the Los Angeles Free Press (number 10

in the book collections), so itís an odd cross between essay and fantasy.

Ellison sees himself getting offed anywhere between April 1973 and 2010, via

a variety of methods from mugging to pneumonia to stomach cancer to freezing

to plane crash to ptomaine poisoning. Along the way, he finishes his long-awaited

magnum opus novel Dial 9 to Get Out (1981), wins Book-of-the-Month

club honors and a film deal for All the Lies That Are My Life (1986),

and is honored on a commemorative postage stamp (some time after 1990, although

most commemoratives, especially the ones issued by the U.S. Postal Service,

require the passage of a decent amount of time after the honoreeís death;

wisely, Ellison doesnít say U.S. postage stamp, and since Princess Diana,

John Lennon, Jerry Garcia, and Disney characters have turned up as revenue-generating

commemoratives from tiny states such as Azerbaijan, Ras al Khaima, and Rwanda,

this one isnít as far-fetched as it sounds).

Ellison did publish a book (a novella) called All the Lies That Are My Life, which first appeared in abridged form in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction (1980) and in a privately printed, 600-copy book edition by Underwood-Miller the same year. Underwood-Miller published a regular edition of the novella in 1989. The title dates from at least 1967, when it appeared in "Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes," first published in Knight magazine. Ellison must have liked it a lot and held onto it until a story came along that it suited as a title. (Parenthetically, Ellison exhibits a fondness for iambic titles, such as this one, and "All the Birds Come Home To Roost," "Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes," "The Song the Zombie Sang," and of course the one lifted straight from† the greatest English iamb-master of them all, "Count the Clock That Tells the Time.")

Thereís also a little science-fiction-y forecasting in these brief six pages. By 1986 home consumers are enjoying a three-dimensional form of television entertainment called holovid, which puts them inside the action, and robot physicians called phymechs do initial diagnostics on hospital patients. (It is left unclear whether they perform actual surgery.) By 1991, a cure for cancer has been found and the disease has become no more serious than the íflu. The only common thread running through many of these fantasies is that the central character has either just finished a major work, or is manically continuing to write up to the moment of death and often regretful that he didnít get time to do more writing.

Although "The Day I Died" isnít terribly witty or memorable, and some of the details are downright fatuous (postage stamp? Nobel Prize?), there remains something very gutsy about envisioning oneís own death in almost a dozen different ways and committing it to paper -- in print, before God and everyone. One of the ultimate fate-daring acts, it strikes me as something few other writers would attempt.

A footnote in the original edition of Stalking the Nightmare states that this piece was almost outdone by reality on May 20, 1982, when Ellison and his assistant Marty Clark crashed in his beloved 1967 Camaro (whose odometer reading had more than tripled since it turned up in the opening paragraph of this essay in1973), but walked away unscathed. You can read a detailed account of the incident in An Edge In My Voice column number 29. The note ends triumphantly: "Having now bypassed the first two demises in this essay, the Author contends he will live forever. This does not delight the Authorís enemies."

To pile on the coincidences, hypothetical death number 7 consists of a sudden, massive coronary (much like his fatherís) in 1990. The verb "bypassed" in the footnote is ironic. In 1992 Ellison, experiencing chest pains, got checked out and had angioplasties performed in June and August. Worse symptoms developed on April 10, 1996, and Ellison had to skip the wrap party for the third season of Babylon 5 (for which he served as Conceptual Consultant), checked into a hospital, suffered a heart attack, and had quadruple-bypass surgery four days later. A 1996 Update footnote in Edgeworks II admits that in 1973 "I didnít have a ratís whisker of an idea what I was talking about" and dismisses the prolonged immaturity that had inspired him to write of living forever. Of the heart attack, he concludes: "I stood right there in the Doorway to Nowhere, and I looked through, and understood -- really for the first time in my life -- that woolgathering exercises like this creaky essay are pure adolescent braggart bullshit."

Reality gave him an additional intimation of mortality with the Northridge Earthquake on January 17, 1994, whose effects he describes at length in the introduction to Slippage.

As of this writing, Ellison has now thumbed his nose at eight of the ten scenarios in "The Day I Died," and bids fair this year to lay the ninth to rest as well (though Iím sure not even he believes he will win a Nobel in this or any other year; in 1999 I put in my plugged two cents with the folks in Stockholm on behalf of the nomination of a writer Ellison much admires, John Fowles, by members of the Comparative Literature faculty of the University of Zaragoza -- the wonders of the Internet -- and look where that got him). As for death number ten, well . . . in 2010 Ellison will have reached a not-implausible 76, and though he wonít be surrounded by grandchildren, and heís given the skinny sonofabitch with the scythe some powerful help with his genetic background and (former) longtime smoking habit, I for one would give him at least even odds.

THREE TALES FROM THE MOUNTAINS OF MADNESS

Tracking Level

Tiny Ally

The Goddess in the Ice

Synopsis

In "Tracking Level," extraterrestrial game hunter and former

shipping magnate Claybourne tracks a fetl on the planet Selangg in the hope

of bringing the six-legged, twelve-inch saber toothed, ring-of-eyes creature

back alive for the Institute, which is paying big bucks because the creature

is rumored to be telekinetic.

Climbers in "Tiny Ally" are near the 18,000-foot mark of Annapurna when they discover the body of a three-inch man in the snow with a knife in the small of his back.

In "The Goddess In the Ice," three climbers discover the body of a beautiful woman frozen in a glacier on an unnamed mountain, chip her out and drag her to a cave, try to imagine how she got there . . . and then she awakens!

Commentary

Three relics from Ellisonís pulpy past: "Tracking Level" dates

from a 1956 Amazing Stories, "Tiny Ally" from a 1957 issue

of Saturn, Magazine of Science Fiction and Fantasy, and "The Goddess

in the Ice" is a non-pornographic reprint from a 1967 Adam Bedside

Reader. Basic science fiction plots. Nothing worth reading twice.

GOPHER IN THE GILLY (Scenes from the Real World: VI)

Synopsis

When Ellison was 13 he ran away from home to join the circus. He didnít

find a circus, he found a traveling carnival, a grimy small-time road show

that traveled in a figure eight between the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois,

Missouri, and Kentucky and was known in the trade as a gilly. Ellison was

a go-fer. Among the cheap thrills the carny had to offer were a fat lady,

a fire eater, a fish boy, and a geek: a wetbrain so far gone into alcoholism

that "his brain has turned to prune-whip yogurt" and he "sweats

sour mash." A geek will do anything for his one or two gin bottles a

day -- dress in animal skin, go without shaving, sleep in a cage, bite the

heads off live animals, wallow in his own excrement -- and what was really

scary to Ellison was how completely the Midwestern crowds were drawn to these

horrific sights. The carnival was busted for various sundry crimes and violations,

and its company bailed everyone but the kid and the geek. Ellison had to spend

three days in a jail cell with that horror, which explains why he has never

taken a drink in his life. It also added to his growing hatred of cops.

Commentary

This is the only piece that appeared in print for the first time with

this book. Thereís no great plot, no lasting lesson for the reader; just a

vivid slice of an era, different in so many particulars from our own, but

perhaps not so different in essence. What are the gilly freak sideshows of

today? Jerry Springer? Ultra-violent films and videos? The Faces of Death

documentaries? The daily auto wrecks that other drivers slow down to see better?

Ellison certainly has had bad experiences with police. Put the even earlier run-in described in "Free With This Box!" together with "Gopher in the Gilly" and a full account of the time one of LAís finest broke his arm (he was covering LBJís speech for Time magazine and punched a cop he saw bothering a pregnant woman with a truncheon, so the officerís buddies moved in), and Ellison would have a pretty good triptych.

In fact, why doesnít Ellison just get around to setting down his memoirs, the long-promised Working Without a Net? With the whole scoop on what it was like doing stand-up comedy and singing in the original Broadway cast production of Kismet, being escorted out of Brazil at gunpoint, driving a dynamite truck and selling porn in Times Square, singing in cabarets with young Barbra Streisand (go ahead, let her have it one more time), being carried out of the desert by Steve McQueen, all the hilarious run-ins with film and television producers (from Irwin Allen to Chuck Barris), the ex-wife who suffered from thanatopsis, the date with a Mardis Gras queen, which fair-weather friend he described at length in the Hornbook installment 21, being held back from the Chicago 7 with Abbie Hoffman, and how did he REALLY get a hold of official Donny Osmond stationery?

There are a helluva lot of us out here who are just dying to read that book, even if it turns out bigger than The Essential Ellison.

Especially if it does.

David Loftus

February 2001

![]()